Ancient Sculptures: India, Egypt, Assyria, Greece and Rome is an international initiative that brings together long-standing partners — the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (CSMVS), The J. Paul Getty Museum, and The British Museum, as well as, for the first time, the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin and Indian museums- National Museum, New Delhi, Bihar Museum, Patna and Directorate of Archaeology and Museums, Madhya Pradesh— to present spectacular works of art from the ancient world. CSMVS in Mumbai has launched a new worldwide educational endeavour. Its goal is to bring significant works of art from other civilizations to Mumbai as witnesses to a shared human past to expand and enrich the study of world history in Indian schools and institutions. The initiative is supported by the Ministry of Culture, Government of India, is open to all from December 2023 to October 2024 and has been scheduled to coincide with the 75th anniversary of Indian independence. This project is part of the Getty’s Sharing Collections initiative, which seeks to foster a truly global understanding of the ancient world. This exhibition highlights similarities in sculptural forms, representation of divinity, and the use of symbolism in ancient India, Egypt, Assyria, Greece, and Rome.

Ancient sculptures

Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalay, Mumbai

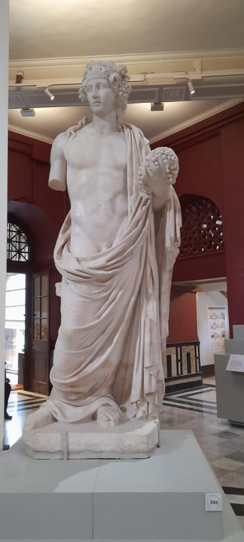

The rotunda welcomes you with the lotus medallion, a magnificent 2nd-century CE limestone sculpture from Amaravati. This lotus, found amid the ruins of the Great Stupa in the Andhra Pradesh capital, is part of a railing with three concentric rows of petals separated by saw-tooth designs and roundels. The core contains the seed container from which the flower blooms. Long before it gained political significance, the lotus symbolised purity across cultures and regions. Step across to the right, ahead of the lotus, and you’ll find a stunning white marble full-figured Dionysos (Greek) or Bacchus (Rome) from 100-199 CE, on loan from the British Museum. There are also busts of all shapes and sizes of gods, including Zeus, Apollo, and Triton, as well as stone panels from Assyria with winged figures. The British Museum’s Egyptian sculpture of Hapy, the deity of the Nile’s inundation, is displayed opposite a digital depiction of the Ganga. While the Nile’s flooding increased land fertility in Egypt, the yearly monsoon in India is critical for crop production and human existence. The pieces interact with one another through their similarities and distinctions.

British Museum

The marble sculpture of the Greek God Dionysus from the British Museum, dating from 100 to 199 CE, is displayed next to a banner showing the Bodhisattva from the Chandigarh Museum. Dionysus, the deity of winemaking, rebirth, and abundance, holds a bunch of grapes that are dropping from his hand. His hair is flowing down his shoulders, and his drape is slipping away as well. These symbols represent a loss of control. The Greeks felt that every human being needed to understand that there are times when we have control and times when we lose it, which is what makes life complete. They imagined their gods and deities to be like these human figures. The Bodhisattva was created around the second century AD in the Gandhara style, with its drape carefully fastened in place. The structure was sculpted during a peak cultural interchange between northern India and Greece, primarily due to Alexander’s visits to the subcontinent. A comparison of these two sculptures reveals that India was absorbing ideas from Greek statues while also developing its own language. The imagery transitioned from symbolic to figurative. A delicate picture of Greek Aphrodite (Roman Venus), the goddess of love and passion, from the Berlin Museum is compared to similar female forms seen on the Hindu temple’s walls, such as apsaras and yakshinis. The museum has chosen to promote the Didarganj Yakshini as a feminine ideal from ancient India.

(Roman Venus),

the goddess of love and passion,

Berlin Museum

The exhibition’s centrepiece is an exquisitely carved red sandstone sculpture of Varaha (wild boar), one of Vishnu’s nine incarnations according to Indian mythology. The sculpture represents the boar rescuing the Goddess of the Earth, Bhudevi, after Hiranya kidnapped her. The scenario occurs in water since the Sheshnaga’s tail extends from Varaha’s back to the front of his body. Saraswati, the Goddess of Knowledge, appears on its snout. When it comes to sustaining the world, it is not enough to simply preserve its physicality; knowledge must also be preserved. Saraswati is depicted here as Vachdevi, the goddess of language. In Indian mythology, animals were occasionally relied upon to represent a deity. Greek gods were often depicted in human form. However, later in Mesopotamia—particularly Assyria (modern-day Iraq and parts of Iran, Kuwait, Syria, and Turkey), which is recognised as the world’s oldest civilization—animal representations were utilised to depict the divine.

Vidisha Archeological Museum,

Madhya Pradesh, India

The museum has to impart knowledge to all its visitors and appoint student docents who walk you through the entire exhibition for a seamless experience. Thus making sure that all the visitors understand the true essence of the exhibition. The museum has also invited multiple renowned scholars to address its visitors through a lecture series to dive deeper into the exhibition’s topic. The positive response from the community to the exhibition and the lecture series is visible clearly through their responses. Notably, this exhibition represents a substantial shift in curatorial perspectives. The purpose is to allow students to encounter art and culture from other regions of the world and to open up new perspectives on their own culture in relation to other societies. This exhibition thus poses to be unique in its true sense.

Encouraging Indian audiences to interact with these ancient sculptures, ask relevant questions, and analyse the pieces using their own cultural understanding could reveal many meanings within these museum artefacts. A second goal of the exhibition is to engage with local schools and institutions, encouraging students and educators to broaden their learning beyond the classroom and to see material culture and museum collections as important sources for historical methodology. This exhibition celebrates humanity’s shared heritage. By bringing together masterpieces from several ancient civilizations, this effort promotes a deep understanding of how art transcends boundaries and time. The exhibition exposes the common links in artistic expression and symbolism across nations and allows Indian audiences to engage with global histories and their own cultural history in fresh and meaningful ways.

The educational outreach provided by student docents and lecture series guarantees that visitors have a better respect and comprehension of these ancient masterpieces. The exhibition intends to change the perception and study of art and history in India by fostering dialogue and critical thinking. This exhibition pays an adequate tribute to the spirit of cultural exchange and learning. It serves as a beacon for future joint efforts, connecting the past and present and opening up new cultural and historical research possibilities.

Reading this, it feels like I am in the museum seeing this sculptures and knowing about them!