Undisturbed for about two millennia, the tomb of the Chinese emperor Qin Shi Huang has been one of the biggest archaeological mysteries.

Originally named as Zhao Zheng, Emperor Qin was born in 259 BC, in Qin state of North-west China. His birth and parentage is shrouded in mystery and his supposed father, king Zhuangxiang, was king of the Qin state. Emperor Qin, reigned from 221-210 BC and successfully took over the six other warring states of China- Chi, Chu, Chao, Han, Wei, and Yan and ultimately unified the Chinese empire. He marked his achievement by proclaiming himself Qin Shi Huang (“First Sovereign Emperor ”). But this empire collapsed only after four years of this death.

Qin Shi Huang was a skilled administrator- he divided the country into administrative units for better administration, appointed officials based on their merit, established a uniform currency, standard weights, as well as a common way of writing. He also made great infrastructural development like a network of roads and canals- the famous Great Wall of China, the terracotta warriors army are all brilliant testaments of his ambitious reign. But his reign had an ugly side too- that being his brutal treatment to dissenting people, scholars and officials.

He was preoccupied with the notion of immortality and took the advice of various chemists, philosophers, alchemists, and even opportunists to achieve his quest. But the search for ‘elixir of life’ eventually led to his death. He is said to have consumed mercury pills to become immortal and this eventually resulted in his death at the age of 49 in 210 BCE.

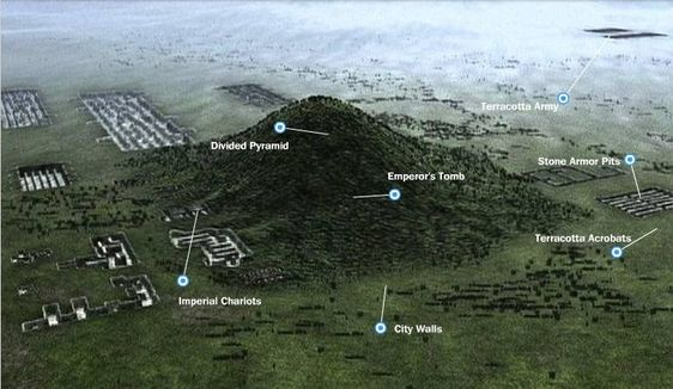

The famous terracotta army that was found accidently, is indeed a fascinating discovery but this is just a part of the mausoleum of Qin. The mausoleum occupies an area of 56.25 square kilometres and is similar to the model of the Qin capital Xianyang comprising an inner and outer city. It is said to have been built in 32 years and involved about 7,00,000 workers. There are about 600 sites within the area and there have been unearthed from the complex- terracotta statues of chariots, horses, officials, acrobats, strongmen, and musicians and also actual bodies of the king’s servants, ministers, concubines- some of which seem to have been forcefully buried. Archaeologists have also found mass graves that appear to hold the remains of the artists and labourers who might have died during the building period- some tied in chains- and also possibly those of the princes killed in power struggle for the throne.

This mausoleum is a source of not only archaeological wealth but also one of the biggest mysteries in history. The mystery is the tomb of the Emperor which has never been opened. Within the mausoleum is a large mound shaped like a truncated pyramid and this covers the tomb of the emperor. Non-invasive studies of the tomb suggest that the tomb is around 80 meters in length, 50 meters in width, and about 15 meters in height.

Insights about what may be hidden beneath can be known from the writings of ancient Chinese historian Sima Qian-

The historian Sima Qian (c. 145–c. 87 BCE) wrote:

‘The labourers dug through three subterranean streams, which they sealed off with bronze to construct the burial chamber. They built models of palaces, pavilions, and offices and filled the tomb with fine vessels, precious stones, and rarities. Artisans were ordered to install mechanically triggered crossbows set to shoot any intruder. With quicksilver, the various waterways of the empire, the Yangtze and Yellow Rivers, and even the great ocean itself were created and made to flow and circulate mechanically. With shining pearls, the heavenly constellations were depicted above, and with figures of birds in gold and silver and of pine trees carved of jade the earth was laid out below. Lamps were fuelled with whale oil so that they might burn for the longest possible time.’

Interestingly aligning with this account- soil samples of the mound show high levels of mercury (although some argue it being a consequence of modern industrial pollution). But it must be kept in mind that Sima Qian did not see the interiors of the tomb or the construction process, his writings are more than a century after the emperor’s death. Also, he missed a really important feature- the terracotta army- it finds literally no mention in his writings.

This itching curiosity can be resolved by excavating the tomb- but why has it never been excavated?

Some say it’s a sign of respect to the emperor and also it is highly probable that if the tomb has Mercury Rivers these may pose a threat when the tomb is opened. More importantly, local sources cite that the current methods of excavating a site of this scale would likely result in irreparable damage. The State Administration of Cultural Heritage (SACH) of People’s Republic of China, is instead following a process of research to develop a protection plan before any long-term excavations can take place in the future.

Well written??!!!!!I look forward to reading your next informative article !!