With its pristine hills, serene lakes, eye-catching meadows, spectacular glaciers and glistening streams the state of Uttarakhand is palpably the abode of everything divine. Complementing its rich natural beauty is its equally rich culture. Uttarakhand, also known as Dev Bhoomi, is primarily divided into two regions: Garhwal and Kumaon. The two regions presently serve as administrative divisions of the state and also embrace their own distinctive culture and history.

Garhwal division includes the districts of Dehradun, Haridwar, Rudraprayag, Chamoli, Pauri, Uttarkashi, and Tehri. There is ambiguity regarding the exact origin of the word ‘Garhwal’, but there are speculations that it was called so because of the numerous forts in the region. Prior to 888 BC, there were about 52 ‘garhs’ (forts) ruled by separate independent rulers. It is said that prince Kanak Pal, of the Parmar clan, of Agnivansha Rajputs who belonged to the Malwa region came to Badrinath (in present day Chamoli district) to perform religious duties. The then mightiest king of the region Bhanu Pratap, who was searching for a groom for his only daughter, got her married to Kanak Pal and also handed him his kingdom. Kanak Pal and his descendants then extended their empire by conquering all the garhs. The Kumaon division in addition too possesses an equally engaging history and culture. Including the district of Almora, Champawat, Udham Singh Nagar, Nainital, Bageshwar and Pithoragarh, the division derives its name from the word Kurmavatar (tortoise incarnation of lord Vishnu). The Kumaon region has been ruled by several notable dynasties over the course of history, most notably the Katyuris and Chands. The first rulers were the Kunindas, and they were followed by Katyuri Kings (700- 1100 AD) founded by Vashudev Katyuri. After the disintegration of Katyuri Kingdom, Kurmanchal disintegrated into eight principalities which were divided among the 8 sons of the Katyuri king Bir Deo. In the 10th century, Som Chand established the Chand Kingdom and the whole region was brought together again as Kumaon.

Both, Garhwali and Kumaonis, vied with each other for superiority in the hills and subsequently both the regions were taken over by the Gurkhas in the 1800s and after the defeat of the Gurkhas in Anglo-Nepalese war, became part of British territory, except area of west Garhwal which was given to the Garhwal king, Sudarshan Shah and was known as Tehri Riyasat.

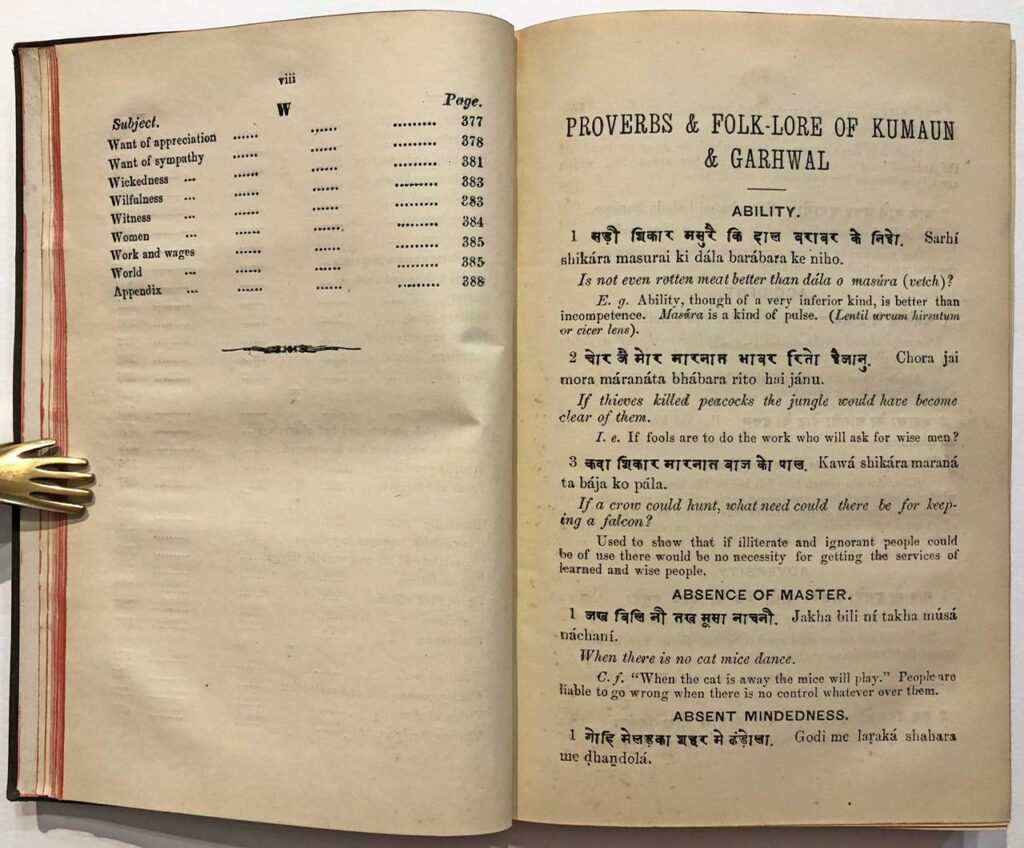

Apart from housing a unique history, both these cultures are endowed with their own distinctively rich attire, cuisine, folklores and language. The language of the people of Garhwal is known as Garhwali. Garhwali’s are considered an ethnolinguistic group and it is considered as an Indo-European language. In modern usage, “Garhwali” is used to refer to anyone whose linguistic, cultural, and ancestral or genetic origins are from the Garhwal Himalayas. The language has evolved over time and its earliest form can be traced back to 10th century BC with its source considered to be Khasas Prakrit. Evidence of Garhwali language has been found in various inscriptions, seals, temple stones, etc. Under the Garhwal kings, Garhwali was the official language of the kingdom. It is sometimes erroneously termed as a Hindi dialect and is presently classified as central Pahari language and it itself has many regional dialects like Badhani, Srinagariya, Chandpuriya, Dessaulya, Salani, Ranwalti, Bhabhari, etc. Similarly the Kumaoni language is also an Indo-European language and is most closely related to neighbouring Garhwali language. It has several dialects, but these, unlike Garhwali, do not differ much from each other. Historically, the Takri script was used to write Kumaoni like other languages with Khasa origin, but it was replaced by Devanagari over time. Kumaoni was the official language of the Kumaon Kingdom.

What might break one’s lingual heart is both of these languages are facing the threat of fading away in the oblivion as villages see large scale out-migration, native speakers switching to dominant languages like Hindi, people losing touch with roots and some simply losing interest. They are no longer the official languages of the state as they enjoyed to be in the past. According to the UNESCO Atlas of World’s Languages in Danger, Garhwali and Kumaoni are in the category of ‘vulnerable language’. Despite being vital languages of the state they are treading the path of extinction, and the threat lurking over other indigenous languages of the state like Jaunsari, Tharu, Raji, Jad, Rangpo, etc. is equally grave.

As aptly expressed in words of Khaled Hosseini – “if culture was a house, then language was the key to the front door, to all the rooms inside.” Language is very well a part of culture. Losing a culture, losing a language is not just the story of Garhwal or Kumaon, many find their echo in the situation that is being faced by Garhwali and Kumaoni. According to UNESCO “one language disappears on average every two weeks, taking with it an entire cultural and intellectual heritage.” There are efforts by some individuals and organizations and to some extent by the political leadership but more organized efforts would be required to prevent these and many other languages to be led down the same road that many “now-extinct” languages had passed through.

It’s really unfortunate that we are losing so many languages… I guess it’s time that we focus more on our vernacular languages.

??well written

wow! This article needs to be read , the way it focuses on how language loss is symbolic to loss of cultural identity today and we need to recognise the value of it . It is so well written and is very much informative .